International support mechanisms and the SpaceAid Framework

International support mechanisms and the SpaceAid Framework

This session aimed at discussing the strengthening of the international coordination with regard to access to existing mechanisms that provide space-based information to support emergency response, such as the International Charter Space and Major Disasters, GMES/SAFER, Sentinel Asia, SERVIR and the UN-SPIDER SpaceAid Framework. Participants were invited to discuss and provide feedback on the utility and timeliness of space-based support for the response and recovery efforts following recent mega-disasters, including direct and fast availability of satellite data and services to the responding organizations, and to provide feedback for improving such support. Key providers and users of space-based data made contributions to this discussion, helping evaluate the present state and making suggestions for better future response efforts. Some of these lines of discussion are reflected in the first chapter of this booklet.

The DLR Center for Satellite based Crisis Information (ZKI): Current status and considerations for the future

The DLR Center for Satellite based Crisis Information (ZKI): Current status and considerations for the future

Harald Mehl, Head of Unit - Civil Crisis Information and Geo Risk, German Aerospace Center (DLR)

Stefan Voigt, Senior Researcher / Teamleader "Humanitarian Relief & Civil Security", German Aerospace Center (DLR)

Introduction

The Center for Satellite based Crisis Information (ZKI) of the German Aerospace Center (DLR) is continuously extending its activities in research, training and operational services to support the use of satellite-based information for disaster management, humanitarian relief efforts and civil security matters. ZKI is engaged in many German and European research and development (R&D) activities. The German Global Monitoring for Environment and Security (GMES) project DeSecure and the European Seventh Framework Programme (FP7) projects Services and Applications for Emergency Response (SAFER) and linkER are currently the most prominent ones among those activities. DLR has formally joined the International Charter Space and Major Disasters in October 2010 and is thus further strengthening the support to international disaster response. The experience in the aftermath of the devastating disaster of the Indian Ocean Tsunami 2004, the Pakistan Earthquake in 2005 or the Haiti Earthquake in 2010 shows that the international community applying satellite information for rapid disaster mapping and assessment is diversifying and is increasingly lacking coordination during extreme disaster situations. In this paper we suggest to establish an international working group, based on the UN-SPIDER network to elaborate and agree to rules of engagement, standards, code of conduct as well as collaborative coordination procedures to improve global efficiency and coherence in satellite-based crisis mapping following extreme disaster situations where many international responders are involved.

ZKI – Current status

General aspects, research and development activities

DLR and its ZKI are continuously working towards further developing the space capacities for the use in the civil security domain, namely crisis- and disaster relief, humanitarian work and security of the citizen. The main activities of ZKI are R&D, data and operational service provision, as well as training and exercises for relief personnel, decision makers, and other stakeholders involved in emergency and humanitarian operations.

In the R&D domain, ZKI has recently completed the coordination and research work of a collaborative project called “DeSecure”, with German partners from industry, academia and public bodies, studying the development and improvement of rapid mapping and space-based emergency response support methodologies. DeSecure was one of the German “De” projects supporting the German contribution to Europe’s GMES initiative, within which DLR is also very actively supporting the qualification and development of the Emergency Response Services (ERS). In the framework of GMES/ERS, DLR/ZKI contributes significantly to the coordination of the respective rapid mapping services through the “SAFER” project, as well as through major contributions to the “linkER” service contract. This service contract was awarded by the European Commission to support the implementation of the GMES/ERS with all 27 member states of the European Community as well as with the respective services at the European Commission’s Directorate General for Humanitarian Aid and Civil Protection (DG ECHO)/Monitoring and Information Center (MIC) and the External Relations Directorate General (DG RELEX). Furthermore, DLR engages in the foreign policy oriented GMES services such as GMOSAIC, addressing international monitoring and policy support topics. In the domain of early warning, DLR, together with its partners, has developed and successfully completed the implementation of the German Indonesian Tsunami Early Warning System (GITEWS) for the Indian Ocean during the years following the devastating tsunami in the Indian Ocean in December 2004.

ZKI operation of services, training and exercises

ZKI continues to further expand the operations of its 24/7 rapid mapping and emergency response services. The GMES/ERS activities form a significant part of our current work at ZKI. Since the last 1 ½ years, GMES/ERS has been activated more than 60 times and the implementation within the European crisis response system is progressing. DLR coordinates the rapid mapping activities within GMES/ERS, which includes not only the operational dispatching and supervision of respective production work, but also covers the planning and implementation of updates, standards and extensions of the rapid mapping services within GMES. Beyond the processing, analysis and mapping work ZKI implements DLR’s support to the International Charter Space and Major Disasters, formally signed by DLR in October 2010. DLR contributes with data from the TerraSAR-X radar satellite mission, as well as through coordination, project management and value adding services to the Charter.

Over the years it has shown that one of the best ways of facilitating the use of satellite mapping products in the emergency management and crisis response community is the engagement in dedicated exercises and trainings at all levels, addressing decision makers, field practitioners, situation centre staff and other stakeholders in the domain. DLR/ZKI is very active in this field and has prepared and conducted a substantial number of exercises and trainings recently, starting from in-house training activities of emergency response staff, exercises with the GMES community of satellite service providers as well as with the national, European and international user community from the civil protection and the humanitarian sector. Exercises have proven to be a very good and essential tool to not only train emergency procedures, but also to identify gaps and possible places for improvement in the analysis and information generation chains, as well as in the application domain of space-based crisis information.

General considerations for improved global coordination of rapid mapping activities in the international response to extreme disasters

General aspects

While a few years ago civilian satellite based crisis information and rapid mapping activities for civil protection and humanitarian purposes were provided by only a few expert centres worldwide, this situation is changing rapidly. Various national, governmental and non-governmental, regional as well as global actors and networks were formed and are more and more engaging in rapid satellite assessment during major crisis situations. These entities are coming from research and academia, industry, public bodies as well as from different UN organizations, etc. The entities operate at different scales and through different communities. While the International Charter Space and Major Disasters (1) has a clear focus on the provision and global synergistic use of space resources, the UN-SPIDER programme, adopted by the UN General Assembly in 2006 (2) aims at global networking, information sharing as well as local and regional capacity building in the domain of space technology for disaster management and emergency response. Beyond those, there are various national and regional/supranational activities such as the European GMES initiative (3) with its “Emergency Response Service” (4) or the Sentinel Asia initiative (5) seeking to achieve regional coordination and cooperation in the field of space technology for disaster response in Asia. Globally speaking, the Group on Earth Observation (GEO) is supporting the development of data sharing and application portals (6). With all these initiatives and the multitude of actors in this field, the awareness and the availability of space-based resources in disaster management increased significantly over the past years. Data access became easier and will continue to become easier. Furthermore the response time of space systems has noticeably improved.

Having said this, these positive developments also have lead to a significant drawback, when it comes to global coordination of efforts during extraordinary disaster or crisis situations, when large numbers of organizations and relief actors are engaging in the relief work as well as in the satellite and geospatial assessment activities. The aftermath of the Haiti earthquake in January 2010 has shown clearly that the sheer number of maps and analysis products, the sometimes severe inconsistencies (thematically and graphically) and the diversity of the hundreds of mapping products posted on ReliefWeb (7) for this event, lead to a confusion, irritation and discouragement of those users which were supposed to be supported by the mapping and satellite-based analysis products. Similar observations could already be made during the days and weeks after the 2004 tsunami in the Indian Ocean as well as during the major Pakistan earthquake in 2005.

As a result of these developments and the ever increasing and diversifying activities in the domain of satellite-based mapping for disaster and crisis management it becomes clear, that the community of space data providers, analysis and mapping centres/networks need to identify, agree and adopt common rules of engagement and coordination to improve coherence, effectiveness, quality, usability and reliability of international space response for extraordinary disaster situations.

Current situation in global coordination

Currently there is no single mechanism in place to warrant proper coordination of international efforts in the response to extreme disasters or crisis events within the geospatial and satellite domain. The different organizations involved, coordinate with each other on an ad-hoc basis, according to personal knowledge and understanding of the individuals involved. While most of the individual organizations and networks within themselves have clear rules of engagement, quality assurance, training, etc., such rules are missing on an international and global scale. Telephone conferences and e-mail lists, as well as a multitude of individual web sites serve as information-, data-, and product exchange tools. The map section of ReliefWeb in its current form basically hosts mapping and analysis products which become available for a specific disaster without having the capacity to verify, validate or aggregate information which may be in some cases redundant, poorly displayed, or in the worst case wrong or contradicting.

Of course, this type of ad-hoc coordination and best-effort based placing of products has been the best possible way of collaboration within the relatively young community of space-based disaster mapping. However, the community and the respective activity level have grown over the last years. Therefore it is time to make a further step towards a better global coordination, standardization and collaboration in rapid mapping for extreme disaster events, involving a large number of international actors.

The way towards generally accepted rules of engagement, standards and coordination

What could be done

The following considerations address the whole community of geospatial information providers and processing organizations making use (even if only partially) of satellite imagery in a rapid response mode for extreme disaster situations, producing information and mapping products meant for public and generic use in this context. Whenever rapid mapping centres generate maps for individual users only, without publishing them on the web, or when it can be ensured that only local or regional actors are involved in the assessment and response work for a given local disaster, no further coordination among international networks and/or organizations is needed. Having said this, probably 90% of the work being carried out globally today in the domain of rapid space-based disaster response mapping will remain unchanged, as it is assumed to be guided under local, regional or individual mechanisms or contracts ensuring the required quality, standardization and responsiveness. The strong need for a global coordination, harmonization and quality assurance emerges for those estimated 10% of the global rapid mapping efforts, dedicated to the before-mentioned extreme disasters, involving a multitude of responders and actors. In those cases, the community urgently needs to move from ad-hoc coordination to a structured way of professional response at a global scale. The community is mature enough to take a next step as well as a next level of quality and coherence.

The challenge resides with the diversity and complexity of the individual players involved, as well as with the heterogeneity of the different data provision mechanisms and the many different technical, organizational and political aspects of the satellite-based rapid mapping activities, especially during large scale events. In order to reach a next level of cohesion in this context, it is suggested to elaborate a minimum level of rapid mapping standards, clear rules of engagement and a code of conduct, which all actors need to respect when engaging under the umbrella of this international collaborative frame. Beyond this, it is absolutely vital to establish a tool for international coordination of the satellite mapping community, without creating a new monolithic institution, claiming the right of command and control for international response efforts. To avoid the formation of such an institution it is suggested to move towards the establishment of clear rules, standards and collaboration through an international working group which has the mandate of elaborating, defining and possibly reviewing such rules, as well as setting up a virtual coordination platform coordinated jointly and during individual events e.g. on a rotating and largely collaborative basis.

Defined capacities and contributions

To start with, a mandated group of international key actors, with representatives from a number of countries, from the UN, and possibly even large international bodies or well recognized NGOs would need to sit together and elaborate jointly the basic rules of engagement, standardization, coordination and collaboration under this international space response framework. The UN-SPIDER programme could be used as the basis for organizing and facilitating the work of this international working group. Such a working group would probably be established for the duration of a year or two, with working meetings every three to six months, elaborating the aforementioned key elements of coordinated international collaboration within the space-based mapping response domain:

- Definition of capacities and key contribution to be coordinated within the process: data provision, processing, analysis, validation/quality assurance, field support, coordination, etc.,

- Definition of rules of engagement, standards and code of conduct,

- Establishment of an internationally accepted, non-discriminating and effective coordination and collaboration mechanism.

It is extremely important to note, that through the establishment of this working group, none of the existing mechanisms, networks, or services should be replaced or marginalized. It is more that these different efforts should be brought together in an effective way, for an even better synergy and coherence in the case of extreme disaster events. The INSARAG Guidelines (8) as well as the UNDAC Handbook (9) may serve as reference documents and examples on how such collaboration may be guided and established.

Coordination, training, exercises and certification

Especially the improved and structured coordination and collaboration will be the key to success in the efforts of establishing a global mechanism of satellite based rapid mapping, without imposing on the individual freedom of action of all contributing parties. However, it is considered a must to establish a collaborative environment of all the existing networks (Charter, GMES, Sentinel Asia, GEO…) where trust and joint work for the greater good are the key drivers in managing and coordinating the global efforts during an emergency operation.

Different ways of organizing a collaborative coordination could be considered for such a mechanism. These could involve a principle of rotation for the coordination of joint efforts within the mechanism, based on a pool of trained, experienced and certified coordinators from different organisations globally. Furthermore, a common coordination platform, such as the Virtual OSOCC on ReliefWeb (7) used among the international relief field teams, will also play a key and central role in setting up this agreed and accepted global coordination.

A good way of achieving internationally agreed standards and common rules is to train everyone according to common guidelines and agreed procedures. Only if the established rules and guidelines are well implemented, well known and adopted by all major actors in the community, the mechanism will work. Thus, training, exercising and certification of the respective capacities which are defined within the mechanism will help to raise the common understanding and ensure that the code of conduct is adopted, quality goals are met and that the minimum level of standardisation is achieved.

Conclusion and perspective

Concluding these considerations it has to be acknowledged that the international community in space- and satellite-based disaster mapping and crisis response has already achieved remarkable progress in responsiveness, capacity and efficiency during the past years. As a result of this progress and in sight of the fast development of DLR/ZKI during the past years from a research entity to an operational crisis mapping service, it is recommended to aim for a commonly accepted global mechanism for coordination of the rapid mapping community in case of extreme disaster events. It is understood that such coordination can only be established on an international and multilateral basis, with all major actors taking on their responsibility, contributing a good part of their respective capacity to the global efforts and agreeing to the setting up of a light and efficient cooperation mechanism.

It is recommended to establish an international working group, with a clearly defined high level representation of the relevant groups and experts, to develop, agree and establish international rules of engagement for space-based rapid mapping efforts at the global level. The community is ready to take the next step and time is short, as the next extreme disaster event can happen tomorrow.

References

- www.disasterscharter.org

- www.oosa.unvienna.org/oosa/unspider/index.html

- www.gmes.info

- www.emergencyresponse.eu

- http://dmss.tksc.jaxa.jp

- www.earthobservations.org

- www.reliefweb.int

- www.usar.nl/upload/docs/insarag_guidelines_july_2006.pdf

- http://ochaonline.un.org/OCHAHome/AboutUs/Coordination/UNDACSystem/UNDACHandbook/tabid/6012/language/en-US/Default.aspx

The International Network of Crisis Mappers

The International Network of Crisis Mappers

Jen Ziemke, Co-Founder, International Network of Crisis Mappers

The Network

The International Network of Crisis Mappers (www.crisismappers.net) is the world’s premier hub for crisis mapping and humanitarian response. The network brings together a diverse set of individuals from the humanitarian, human rights, policy, technology, and scholarly communities, to help catalyze communication and collaboration between and among a wide range of different communities with the purpose of advancing the study and application of crisis mapping worldwide. We are excited by the possibility of continuing our collaboration with UNOOSA/UN-SPIDER on current and future initiatives and were very happy to attend the latest workshop in Bonn.

Throughout the year, the Crisis Mappers Network facilitates continuing virtual interaction among its members. Participants engage the community through monthly webcasts, create and browse profiles, e-mail their needs through our dedicated Google Group, and write blogs and share other announcements with the Group. As of October 2010, the Network had grown to over 1,000 members from over 30 countries across 6 continents. We encourage interested members of the UN-SPIDER community to join the Network. We need your advice and respect your unique expertise in this domain. We are excited by the new innovations that emerge from working together and leveraging our collective knowledge.

We are a volunteer-led, loose horizontal network of engaged individuals committed to working together and learning from one another, and overcoming the problem of informational and institutional silos.

Our value-added

Members of the Crisis Mappers Network revolutionized disaster response in the way they mobilized and collaborated following the earthquake in Haiti in 2010. An excellent overview of the unprecedented role played by the Crisis Mappers Group in Haiti, which helped save hundreds of lives is given in “Measuring our Response: An Executive Summary”, which is available on Google Docs (1). None of this would have been possible without the first International Conference on Crisis Mapping, in Cleveland in October 2009. The conversations that began in 2009 at the conference helped shape a culture of sharing, trust, openness, dialogue, and a commitment among our members that helped enable the remarkable volunteer community response that ensued. Members shared the very latest aerial and satellite imagery, their professional and technical expertise, and countless hours of their time. If someone requested help of our network, within less than an hour typically someone in the community would offer their assistance. Thousands of e-mails, tweets, blog posts, and Skype chats directly helped facilitate humanitarian response on the ground.

This response has certainly not been limited to the crisis in Haiti or just to the Crisis Mappers Network. Several other networks like our friends at Crisis Commons have been integral to this new movement as well. Over the past year, the community broadly defined also proved its continuing capacity to contribute to effective disaster response in the wake of destructive floods, typhoons, conflict, chronic poverty, a cholera epidemic, and after crippling snowstorms and devastating oil spills.

The Crisis Mappers also continue to work on issues related to elections, fraud, and community engagement in repressive regimes. In short, they are brainstorming creative solutions to some of the world’s most complex problems. Please keep in mind these efforts are new and only mark the beginning of what will be a long, evolving process. We need your help identifying and coping with the practical, political, ethical and technical issues that have emerged.

The Conference Series

The International Network of Crisis Mappers convenes an annual conference series, to bring together the most engaged practitioners, scholars, software developers and policy makers at the cutting edge of crisis mapping and humanitarian technology to address and assess the role of crisis mapping and humanitarian technology in disaster response. The inaugural conference took place at John Carroll University in Cleveland Ohio in October 2009. The second annual event was convened at Tufts and Harvard Universities in Boston, Massachusetts in October 2010.

These annual conferences facilitate collective engagement and dialogue that helps construct the boundaries of this emergent new discipline. At the conference, participants also brainstorm how to solve real problems and initiate projects to help advance this new field.

Sections/Discussions

The public portion of the conference begins with an engaging set of five-minute ignite talks, in order to familiarize everyone with the exciting work being done in this space, and in order to maximize value, networking, and interactivity. At ICCM 2010 in Boston, we heard special remarks from the first Chief Information Technology Officer of the UN, Assistant Secretary General Dr. Choi Soon-hong. Our keynote speaker, Kurt Jean Charles, then offered a remarkable first-hand account of what his Haitian technology company did to help save lives after the earthquake. Videos of all ignite and keynote talks from the conferences in 2009 and 2010 are available on the Crisis Mappers homepage (2).

The first day of the public conference also includes an interactive Technology and Analysis Fair that enables participants to directly engage with several different platforms and academic analyses of Crisis Map data. Sessions over the three days are structured to allow ample time for networking and collaboration over breaks and meals.

The invitation-only Annual Meeting kicks off with a series of roundtables meant to explore lessons learned and where to go from here. In 2010, over 20 creative self-organized sessions which were organized and initiated by participants themselves really helped advance and create future directions for this field.

ICCM 2011 builds on highly diverse attendance in 2009 and 2010

Our list of attendees from past conferences span a diverse field, including representatives from: the United Nations Office of the Secretary General, UN Global Pulse, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the UN Development Programme (UNDP) Sudan, UNOOSA/UN-SPIDER, the Operational Satellite Applications Programme of the UN Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR/UNOSAT), the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the World Food Programme (WFP), the UN Foundation, the World Bank, Sustainable Technologies, Accelerated Research - Transformative Innovation for Development and Emergency Support (STAR-TIDES), ICC, EU's Joint Research Center (JRC), NATO, International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), American Red Cross, Human Rights Watch, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM), Freedom House, US Department of Homeland Security (DHS), US Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), United States Geological Survey (USGS), US Department of State, US Agency for International Development (USAID), American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, Google, ESRI, Amnesty International, Microsoft, Vodafone, IBM, Reuters/AlertNet, International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), New York Times, InterNews, InterAction, Meedan, FortiusOne, GeoCommons, Humanitarian Accoord, iMMAP, Digital Democracy, ImageCat, InSTEDD, Ushahidi , ReliefWeb, Plan West Africa, Sahana, GeoTime, Digital Globe, Mercy Corps, ICT4Peace, Map Kibera, CDAC Haiti, Louisiana Bucket Brigade, NiJeL, FrontlineSMS, OpenGeoSpatial, OpenStreetMap, Solutions.ht, Konpa Group, Development Seed, HealthMap, Tufts, Columbia/SIPA, Tulane, University of Sussex, Carnegie Mellon, Berkeley, National Defense University, UCLA, Stanford, Princeton, Harvard Center for Geographic Analysis, MIT Media Lab, and Crisis Commons.

ICCM 2010 was sponsored by Humanity United, the Open Society Institute, the United States Institute of Peace, the Knight Foundation, Google, ESRI, Ushahidi, the World Bank, the Hitachi Center, the Fletcher School at Tufts University, and GeoTime. The Harvard Humanitarian Initiative and John Carroll University convened the annual conference series in 2009 and 2010.

Our niche

The new field of Crisis Mapping encompasses the collection, dynamic visualization and subsequent analysis of geo-referenced information on contemporary conflicts and human rights violations. A wide range of sources are used to create these crisis maps, such as events data from newspaper and intelligence parsing, satellite imagery, interview and survey data, SMS, etc. Scholars have also developed analytical methodologies to identify patterns in dynamic crisis maps. These range from computational methods and visualization techniques to spatial econometrics and “hot spot” analysis.

While scholars employ these methods in their academic research, operational crisis mapping platforms developed by practitioners are typically devoid of analytical tools. At the same time, scholars often assume that humanitarian practitioners are conversant in quantitative spatial analysis, which is rarely the case. In other words, there is a notable divide between scholars and practitioners in the field of crisis mapping and any division slows the progress of a new field. The purpose of the Network and the conference series is therefore to continue to bridge the divide by bringing scholars and practitioners together to shape the future of crisis mapping.

We hope that the Network and conference series is just the start of many new collaborative ideas that emerge when we work together rather than in isolation from one another. We look forward to many new developments in this space in the months and years to come. We hope you join us!

References

- Measuring our Response: An Executive Summary, on: http://docs.google.com/Doc?docid=0ATKkO3odnjoeZGd2OWpna2NfNTZnY2RiaHhkcQ&hl=en (last viewed 10 November 2010)

- Ignite talks of ICCM 2010, on: http://www.crisismappers.net/video (last viewed 10 November 2010).

Overview of the flood situation in West Africa in 2010: the role of spatial information management

Overview of the flood situation in West Africa in 2010: the role of spatial information management

Abdoulaye Dieye, GIS Officer, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Regional Office for West and Central Africa (UNOCHA/ROWCA)

Context

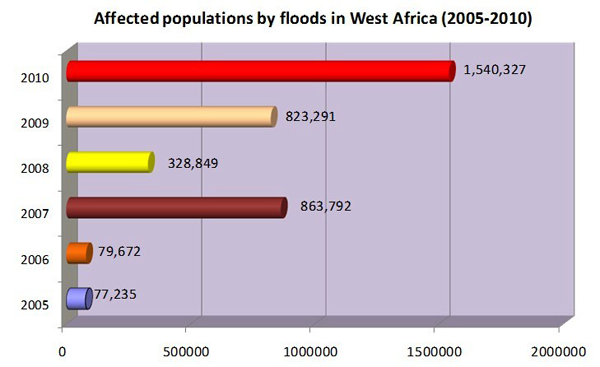

Since 2007, the flood situation in West Africa is becoming more and more recurrent and the impact on the population and infrastructures is becoming more severe.

Figure 1: Flood affected populations in West Africa during the last 5 years. Sources: Data from 2005, 2006, 2008: CRED. Data from 2007, 2009, 2010: OCHA.

Since 2009, the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs/Regional Office for West and Central Africa (UNOCHA/ROWCA) has been working closely with the UN Platform for Space-based Information for Disaster Management and Emergency Response of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs (UNOOSA/UN-SPIDER), other UN entities (the World Food Programme (WFP), the Operational Satellite Applications Programme of the UN Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR/UNOSAT), etc.), members of the International Charter Space and Major Disasters (International Charter) for obtaining satellite imagery and rapid mapping, members of the European Services and Applications for Emergency Response (SAFER), governments, and NGOs to support emergency response and risk reduction efforts with geospatial information and rapid mapping.

Flood impact profile in West Africa in 2010

The year 2010 is generally marked by a relative humidity higher than in previous years with heavy rains between June and October over the sub-region of West Africa. Devastating floods are observed in almost all countries of the sub-region with over 1.5 million affected people and over 300 deaths. Significant damages were also noted on socio-economic infrastructures with houses, roads, bridges, hospitals, and schools destroyed, thousands of hectares of farmland and crops washed away, and livestock decimated. Benin is the most affected country with about 690,000 affected people, 86 deaths and 86,000 hectares of farmland damaged. Benin is followed by Nigeria (300,000 Internally Displaced Persons), Niger (226,000 affected people), and Burkina Faso (over 105,000 affected people).

Figure 2: Map of floods impact profile in West Africa

Mechanism of coordination and communication for geo-spatial information and rapid mapping support

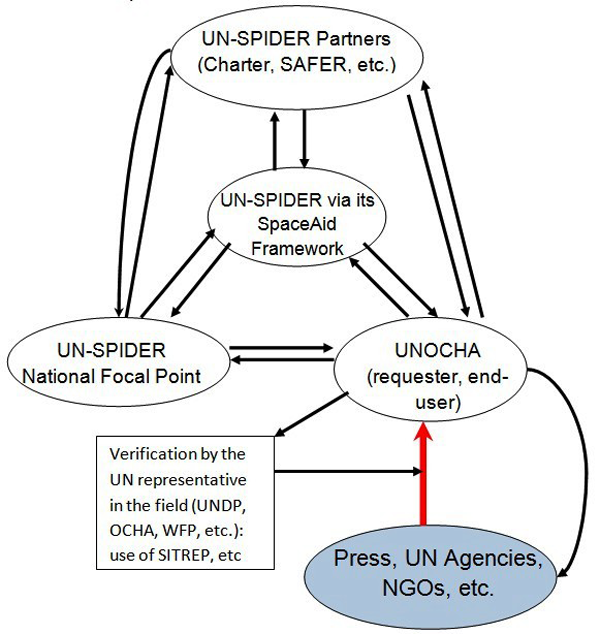

Within their respective roles to facilitate the coordination of humanitarian affairs and space affairs, UNOCHA/ROWCA works closely with the UNOOSA/UN-SPIDER to facilitate the activation of mechanisms for spatial information and rapid mapping support (the International Charter, SAFER, etc.) in West Africa.

Mechanism used by UNOCHA to request Charter and SAFER activation in Burkina Faso, Senegal and Benin in 2010

After an alert from the press, local UN Offices, NGOs, or the Government, UNOCHA requests support through the UN-SPIDER SpaceAid Framework and indicates its needs in consultation with UN-SPIDER experts and the UN-SPIDER National Focal Point. UN-SPIDER forwards the request to all partners of the Framework. The project manager who is nominated by the providers (UN-SPIDER partners) works closely with the different stakeholders (UN-SPIDER, UNOCHA, Government). The maps and spatial data are disseminated on the Knowledge Portal and the links are shared to UNOCHA and the National Focal Point as end users. These products are shared to humanitarian partners (UN Offices, NGOs, governments, etc.) to facilitate their activities in the field. A user feedback form is filled in at the end of the support mechanism to evaluate the process.

Figure 3: Schematic of the mechanism used to activate SAFER and the International Charter for Burkina Faso, Senegal and Benin.

Examples of spatial information and rapid mapping support in West Africa

In 2009, the International Charter was activated to obtain satellite imagery and support in rapid mapping for Benin, Senegal, Burkina Faso, Niger and Mauritania.

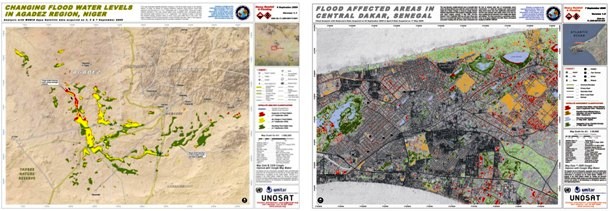

Figure 4: Maps of flooded areas in Agadez (Niger) and Dakar (Senegal) obtained after processing of satellite images from the International Charter.

In 2010, SAFER has been activated for three countries (Burkina Faso, Niger and Senegal), the International Charter for two countries (Benin and Nigeria).

Figure 5: Maps of flooded areas in Sampelga (Burkina Faso) and Dakar (Senegal) obtained after processing of satellite images from SAFER, and Cotonou (Benin) from the International Charter.

These activations were supported by UN-SPIDER as well as by the European Union, the European Space Agency (ESA), the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the German Aerospace Center (DLR) and others. The image processing and rapid mapping were done by UN-SPIDER partner institutions (DLR for SAFER, UNITAR/UNOSAT and the Pacific Disaster Center for the International Charter).

The UN-SPIDER SpaceAid Framework

The UN-SPIDER SpaceAid Framework

David Stevens, Programme Coordinator, United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, United Nations Platform for Space-based Information for Disaster Management and Emergency Response (UNOOSA/UN-SPIDER)

When an emergency happens there is an urgent need to assess impacts and requirements as soon as possible. Space-based technologies provide innovative ways to generate information to respond to this need. Earth observation and meteorological satellites continuously image the Earth. If tasked to acquire imagery over disaster areas, these satellite-based sensors can rapidly help evaluate the extent of the impact caused by the disaster, thereby ensuring rescue efforts are sent to the right place. Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) support response teams by helping them reach the disaster area (navigation) and also by providing the means of registering on a map the location of anything the response team needs to locate geographically (positioning). Finally, satellite communication provides a valuable alternative to land-based communication systems.

Figure 1 – Impact of the Chile Earthquake 27 February 2010

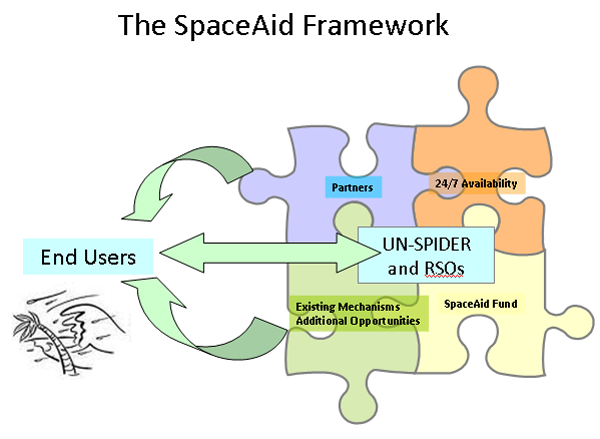

There are a number of available mechanisms and initiatives that help countries receive relevant information and access space-based technologies to support response efforts, such as the International Charter Space and Major Disasters, Sentinel Asia and Télécoms Sans Frontières. In 2009 the UN-SPIDER Programme initiated the SpaceAid Framework to help countries as well as international and regional organizations benefit from these technologies and this type of information, specifically to:

a) Ensure that all end users are able to access these mechanisms and initiatives, on a 24 hours a day/7 days a week basis, and that they also have the capacity to use all space-based information made available to support emergency events;

b) Provide guidance to the existing mechanisms and initiatives on the specific requirements of the end users and also on how they could improve and extend their support;

c) Establish additional opportunities beyond what is currently available within the existing mechanisms, and;

d) Provide information to those interested in providing support (space-based information and expertise) on how they could channel their support and to whom.

The UN-SPIDER Programme is uniquely positioned to implement and promote this framework:

a) The Programme has been specifically mandated by the United Nations General Assembly to ensure that all countries are able to access space-based information to support emergency response. To this end, since 2007 the Programme has built working relationships with national and regional space agencies, international mechanisms, and technical organizations capable of generating such type of information;

b) The Programme derives strength from a network of UN-SPIDER Regional Support Offices which ensures that end users can access expertise regionally. In its resolution 61/110, the United Nations General Assembly agreed that UN-SPIDER should work closely with regional and national centres of expertise in the use of space technology in disaster management to form a network of Regional Support Offices for implementing the activities of UN-SPIDER in their respective regions in a coordinated manner;

c) Currently, the Office for Outer Space Affairs has signed cooperation agreements with Algeria, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Nigeria, Pakistan, Romania, Ukraine, the Asian Disaster Reduction Center (ADRC), the Regional Center for Mapping of Resources for Development (RCMRD), the Water Center for the Humid Tropics of Latin America and the Caribbean (CATHALAC) and the University of West Indies, formalising the establishment of ten Regional Support Offices worldwide;

d) The Programme has established a network of UN-SPIDER National Focal Points. A National Focal Point is a national institution nominated by the Government of the respective country, representing the disaster management and space application communities. The role of National Focal Points is to work with UN-SPIDER as well as with UN-SPIDER Regional Support Offices to strengthen national disaster management planning and policies and implement specific national activities that incorporate space-based technology solutions in support of disaster management;

e) The UN-SPIDER Knowledge Portal (www.un-spider.org) is central to all activities of the UN-SPIDER Programme as in essence it provides the hosting environment and dissemination tool for all these activities and the resulting outputs and products. Specifically to support SpaceAid, a separate webpage is created for every event and the following information included: information on the event, available value-added products, available pre- and post disaster images, UN-SPIDER contact points, including the Regional Support Office, information on sensor tasking, available geospatial data sets, vector data of impacted areas, and other space-based information and technologies, and;

f) The UN-SPIDER Programme supports countries directly by carrying out Technical Advisory Missions to countries that request such support.

The work of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs in relation to disaster management and emergency response is driven by resolution 61/110 which established the United Nations Platform for Space-based Information for Disaster Management and Emergency Response, known as UN-SPIDER. The accomplishment sought by the programme of work being implemented by UN-SPIDER is greater understanding, acceptance and commitment by countries on ways of accessing and developing capacity to use all types of space-based information to support the full disaster management cycle. UN-SPIDER has been established through this resolution to act as a gateway to space information for disaster management support, to serve as a bridge to connect the disaster management and space communities, and to act as a facilitator of capacity-building and institutional strengthening, in particular for developing countries.

UN-SPIDER staff together with the UN-SPIDER Regional Support Offices is implementing the SpaceAid Framework. The Framework aims at:

a) Ensuring that all end users can access and use all space-based information made available to support emergency events by existing mechanisms and initiatives. Importantly the end users have to be able to access and receive this support on a 24 hours a day/7 days a week basis. The space-based information has to be available to support early warning (monitoring), emergency and humanitarian response as well as early recovery;

b) Providing guidance to existing mechanisms and initiatives on how they could improve and extend their support, as well as establishing new opportunities;

c) Ensuring that providers of space-based information and expertise know who to provide support to.

As depicted in Figure 2, the SpaceAid Framework is built on four cornerstones:

Figure 2 – The SpaceAid Framework

- Existing mechanisms and additional opportunities with which UN-SPIDER establishes cooperation agreements and arrangements to access and make available to end users space-based information and value added products as well as other space-based solutions and technologies;

- An operational 24 hours a day/7 days a week emergency hotline which can be accessed through telephone, e-mail or fax to which end users can send their request for support. Additionally there is the need to ensure that all relevant information is made available immediately to the end users as well as to those interested in providing support;

- Partnerships, in addition to ones established with the UN-SPIDER Regional Support Offices, with leading centres of excellence (national and regional) as well as academic institutions, non-government organisations and private companies willing to provide support to analyse the space-based information and provide scientific and technical expertise to end users, and;

- The SpaceAid Fund which would enable the framework to provide support beyond what is currently possible and also to ensure rapid and direct acquisition of satellite imagery as well as other space-based technologies to support emergency and humanitarian response in cases when existing mechanisms could not provide the full extent of what is required, such as when users need to receive imagery from specific sensors or when there is a need to have multi-agency licenses, as well as for humanitarian response, early recovery and reconstruction.

Existing mechanisms and initiatives

The UN-SPIDER Programme already has in place agreements and arrangements with several of the global and regional initiatives including the International Charter Space and Major Disasters (UNOOSA has been a cooperating body to the Charter since 2003), Sentinel Asia (UNOOSA is a member of the Joint Project Team), and the GMES Project “Services and Applications for Emergency Response” (SAFER). Additionally, UN-SPIDER ensures cooperation with another relevant GMES Project “GMES services for Management of Operations, Situation Awareness and Intelligence for regional Crises” (G-MOSAIC) and works closely in promoting and leveraging upon the opportunities provided by the regional SERVIR projects.

The SERVIR Regional Visualization and Monitoring System integrates Earth observations and forecast models together with in situ data and knowledge for timely decision-making to benefit society, particularly to support disaster management. SERVIR is being implemented regionally in Latin America and the Caribbean by CATHALAC, in Eastern Africa by RCMRD, and in the Himalaya region by the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) in Nepal. Both RCMRD and CATHALAC are UN-SPIDER Regional Support Offices, which ensures close coordination and strengthens the regional work.

The UN-SPIDER Programme works closely with the above projects and initiatives, promoting them with end users and ensuring that these end users establish direct working relationships with such mechanisms. Additionally, the UN-SPIDER Programme provides guidance to these projects on how they could improve and extend their support to meet the need of the end users.

Building additional opportunities and partnerships

In providing support to countries the UN-SPIDER Programme takes advantage of additional opportunities governments, non-governmental organisations and the private sector are making available and also ensures the involvement of leading centres of excellence to support the analysis of the space-based data being made available.

China has offered direct access to its satellites HJ-1A and HJ-1B and has already provided imagery to support several emergencies. Additionally, the UN-SPIDER Programme has worked closely with several providers of space-based imagery including NASA, DLR, RapidEye, Scanex, Digital Globe and GeoEye, facilitating the access of data made freely available by these providers to the end users.

In providing support to countries the UN-SPIDER Programme aims at involving the UN-SPIDER Regional Support Offices and other centres of excellence that are in a position to support the analysis of the data and in the production of the maps and value-added products.

Figure 3 – UN-SPIDER Regional Support Offices – 1st Meeting 09 February 2010

Support provided in 2009 and 2010

In 2009 the SpaceAid Framework supported a total of 20 events globally (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Burkina Faso, El Salvador, Fiji, Guatemala, Indonesia, Iran (Islamic Republic of), Italy, Lao PDR, Morocco, Namibia, the Philippines, Samoa, Senegal, Tajikistan and Vietnam). In the first 10 months of 2010 a total of 25 emergency events have already been supported including the two devastating earthquakes that hit Haiti and Chile (Benin, Burkina Faso, Chile, China, Cook Islands, Gaza oPt, Guatemala, Haiti, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Madagascar, Moldova, Pakistan, Senegal, Solomon Islands, Sri Lanka, Sudan, Tajikistan, Tonga, Turkey, Uganda and Ukraine).

The evident increase in the number of events supported by the SpaceAid Framework is due to the implementation of standard operating procedures which contributed to the streamlining and optimisation of the support provided, the establishment of additional agreements and arrangements with existing mechanisms and opportunities, and the increasing expansion of the network of UN-SPIDER Regional Support Offices which brings in additional expertise and resources.

In order to be able to receive funds that will support the functioning of the SpaceAid Framework, particularly to ensure rapid and direct acquisition of satellite imagery as well as other space-based technologies to support emergency and humanitarian response in cases when existing mechanisms could not provide the full extent of what is needed, the Office for Outer Space Affairs set up a specific account within the existing “Trust Fund in Support of United Nations Space Applications Programme”. This fund will complement the existing opportunities, ensuring that all countries in the world are able to request and receive space-based information to support all emergency and humanitarian response activities.