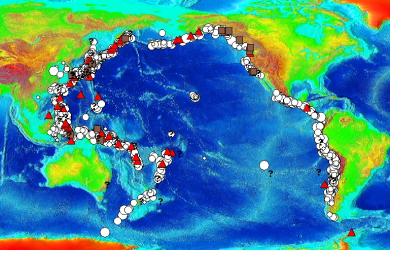

Many countries in the world are vulnerable to teletsunamis, or trans-ocean tsunamis. Some seismic waves travel through the earth and reach sensors anywhere in the world more or less at the same time. Therefore, theoretically, detection and monitoring can be done in one location for the whole world. In reality, these activities are duplicated.

Tsunami-detection buoys transmit data through satellite, meaning that they arrive more less seconds apart in different locations depending on how many hops are needed. But clearly the four- and nine-minute warnings that were issued by the two agencies on the March 11 were based solely on earthquake data, not data transmitted from tsunami-detection equipment.

It is when it comes to interpretation that national centers are important. Setting off sirens and broadcasting warnings on cellphones will help people evacuate, but can also trigger mass panic, cause heart attacks in a subset of the populace and disrupt normal life.

Tsunami prediction is an inexact science and false alarms can have major negative consequences. Only national authorities can make the call on issuing evacuation orders. This is what concerned professionals and the media must focus on, not on whether each country has its own tsunami detection and monitoring buoys.