Researchers at the University of Illinois have become the first to record an airglow signature in the upper atmosphere produced by a tsunami using a camera system based in Maui, Hawaii.

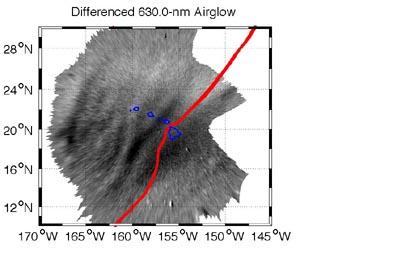

The signature, caused by the March 11 earthquake that devastated Japan, was observed in an airglow layer 250 kilometers above the earth's surface. It preceded the tsunami by one hour, suggesting that the technology could be used as an early-warning system in the future. The findings were recently published in the peer-reviewed Geophysical Research Letters.

The observation confirms a theory developed in the 1970s that the signature of tsunamis could be observed in the upper atmosphere, specifically the ionosphere. But until now, it had only been demonstrated using radio signals broadcast by satellites.

"Imaging the response using the airglow is much more difficult because the window of opportunity for making the observations is so narrow, and had never been achieved before," said Jonathan Makela, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and researcher in the Coordinated Science Laboratory. "Our camera happened to be in the right place at the right time."

Tsunamis can generate appreciable wave amplitudes in the upper atmosphere - in this case, the airglow layer. As a tsunami moves across the ocean, it produces atmospheric gravity waves forced by centimeter-level surface undulations. The amplitude of the waves can reach several kilometers where the neutral atmosphere coexists with the plasma in the ionosphere, causing perturbations that can be imaged.

On the night of the tsunami, conditions above Hawaii for viewing the airglow signature were optimal. It was approaching dawn (nearly 2:00 a.m. local time) with no sun, moon or clouds obstructing the view of the night sky.

Along with graduate student Thomas Gehrels, Makela analyzed the images and was able to isolate specific wave periods and orientations. In collaboration with researchers at the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris, CEA-DAM-DIF in France, Instituto Nacional de Pesquisais Espaciais (INPE) in Brazil, Cornell University in Ithaca, NY, and NOVELTIS in France, the researchers found that the wave properties matched those in the ocean-level tsunami measurements, confirming that the pattern originated from the tsunami. The team also cross-checked their data against theoretical models and measurements made using GPS receivers.

Makela believes that camera systems could be a significant aid in creating an early warning system for tsunamis. Currently, scientists rely on ocean-based buoys and models to track and predict the path of a tsunami.

Previous upper atmospheric measurements of the tsunami signature relied on GPS measurements, which are limited by the number of data points that can be obtained, making it difficult to create an image. It would take more than 1,000 GPS receivers to capture comparable data to that of one camera system. In addition, some areas, such as Hawaii, don't have enough landmass to accumulate the number of GPS units it would take to image horizon to horizon.

In contrast, one camera can image the entire sky. However, the sun, moon and clouds can limit the utility of camera measurements from the ground. By flying a camera system on a geo-stationary satellite in space, scientists would be able to avoid these limitations while simultaneously imaging a much larger region of the earth.

To create a reliable system, Makela says that scientists would have to develop algorithms that could analyze and filter data in real-time. And the best solution would also include a network of ground-based cameras and GPS receivers working with the satellite-based system to combine the individual strengths of each measurement technique.

"This is a reminder of how interconnected our environment it," Makela said. "This technique provides a powerful new tool to study the coupling of the ocean and atmosphere and how tsunamis propagate across the open ocean."