Authorities in Bali, Indonesia have ordered residents living near the Mount Agung volcano to evacuate the area amidst warnings from emergency agencies of a potential major eruption. Indonesia’s advanced hazard early warning and monitoring system, InAWARE, has helped officials anticipate impacts to populated areas and develop evacuation and response plans. However, for the most part, clear predictions for volcanic eruptions remain a difficult task.

Indonesia is located on the western rim of a seismically and volcanically active "Ring of Fire" that traces an outline around the Pacific Basin from New Zealand to the tip of South America. The recent eruption of Mount Agung is a first for the volcano in nearly 50 years, the last eruption in 1963 killing 1,100 people. Senior state volcanologist Gede Suantika said that "[t]he volcano's alert level has been raised to the highest level” and that "[c]onstant tremors can be felt”. Currently, the danger zone encompasses 22 villages and about 100,000 people.

In order to anticipate the impact of the eruption on populated areas Indonesian officials have made use of InAWARE, Indonesia’s early warning and decisio support system. InAWARE is a customized version of the Pacific Disaster Centre’s (PDC) DisasterAWARE platform. It was developed by Indonesia’s national disaster management agency (BNPB) with the support of the United States Agency for Internationa Development Office of Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID).

Nevertheless, one particularly problematic characteristic of volcanic eruptions is that it is nearly impossible to estimate how great the intensity will be. Indonesia's Volcanology and Geological Disaster Mitigation Centre (PVMBG), which is using drones, satellite imagery and other equipment,said predictions were particularly difficult in the absence of instrumental recordings from the last eruption 54 years ago.

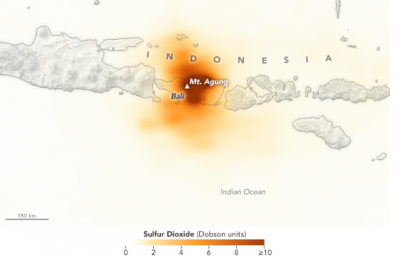

Space-based information still plays an important part in managing such disasters. Satellite measurements help assess gases venting out of volcanoes and show how much the ground over a volcano bulges as magma inside the Earth tries to find an outlet. Seeing whether carbon dioxide is being released from the magma before it releases the surface can potentially give an advanced warning of an eruption. However, measuring how much magma is inside the volcano and whether it is going to increase or gradually wane remains a difficult task to accomplish. Data from the NASA Aura satellite shows high sulfur dioxide (SO2) concentrations from Mount Agung and the NASA Modis satellite has detected a thermal anomaly in the crater of the volcano after constantly scanning the earth’s surface for cloud formations, changes in the carbon cycle, and sources of heat . The ongoing volcanic activity in Indonesia can be seen on this live map.

Although predicting volcanic eruptions is far from being straightforward, a number of past successful predictions and evacuations can show us how the consistent monitoring of seismicity, gas emissions, and changes in the shape and movement of the ground can make a difference. For example, in 1991 Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines erupted after being dormant for nearly 500 years. Over 60,000 people were successfully evacuated before the eruption due to the careful prior analysis of the mountain. Furthermore, in 2010, monitoring of activity at Indonesia’s Mount Merapi led to the evacuation of 70,000 people before the eruption of the volcano.

In the future, scientists hope that by increasing monitoring and by deploying additional sensors and satellites globally we can improve the way we predict volcanic eruptions, thus coming closer to a real-time warning system.